By Kamran Nayeri, February 26, 2014

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/Futurism-Got-Corn-graph-631.jpg) |

| Source: Meadows, D.H., Meadows, D.L., Randers, J. and Behrens III, W.W. (1972) (Linda Eckstein) |

1. Introduction

In his “Understanding the Present-Day World Economic Crisis—An Eco-Socialist Approach,” Section III, Saral Sarkar aims to provide “The Deeper Causes of the Crisis.”

The title of the article is somewhat misleading as it is about what has come to be called the Great Recession in the United States that began in December 2007 and by some accounts continues to this day. It is an argument for natural limits to growth as the cause for the Great Recession.

It is my good fortune to have come to know Saral. Reading his 1999 book Eco-Socialism or Eco-Capitalism: A Critical Analysis of Humanity’s Fundamental Choices was an immensely educational experience for me. He has contributed to Our Place in the World (that I founded and edit), including through sharing his writings. Although we use different frameworks for analyzing and understanding the crisis of our time (for my own view see Economics, Socialism and Ecology: A Critical Outline Part 1and Part 2 ), I believe we share a common vision of a future that can bring about harmony in society and with the rest of nature.

It is in this context that I find Saral’s argument for the causes of the Great Recession unconvincing. In what follows, I will first outline Saral’s argument. Next, I will offer a criticism of it. Finally, I will note what insight the limits to growth offers and delineate some of its limits in understanding and challenging problems posed by the capitalist civilization. I hope this criticism would be an occasion for an enriching discussion for all those who wish to make a difference in making a better world.

2. Saral’s Reasoning

In essence, Saral’s argument is that existing explanations of the crisis are inadequate or “superficial” because the Great Recession is really caused by natural limits to growth not economic or social ones. Below is a summary of Saral’s reasoning broken into three separate claims. I will add key sentences from Saral’s essay motivating each claim for ease of reference but the reader may wish to review the short section in Saral’s essay:

FIRST CLAIM. A SECULAR, LASTING RISE IN PRIMARY COMMODITY PRICES INITIATED THE CRISIS

In the period leading to the crisis, prices of oil and “the energy resources coal, gas and uranium as well as industrial metals like copper, zinc, iron and steel, tantalum etc.” rose sharply.The price increases were secular and lasting rather than cyclical. “These price rises must not be mixed up with the usual inflations of the past, which were triggered mainly by excessively high wage demands of the working people (the so-called wage-price spiral).” “…[T]he main cause of the said price rises is the rise in the extraction costs of the most important raw materials.” (emphasis in original).“Also the environmental services provided by nature for us are important resources for any kind of society…The costs of maintaining such resources in an industrial society have also increased along with the costs of extracting important resources like the ones mentioned above.”

SECOND CLAIM. HIGH PRIMARY COMMODITY PRICES RESULTED IN DECLINE IN PURCHASING POWER OF MOST PEOPLE

“The rising costs of extracting or conserving these resources mean that less and less of them are available to most people.”

“…[I]f one says that a person’s real income is going down, then it is tantamount to saying that this person is getting less and less resources…” “This exactly is happening today in most of the world.”

“Moreover, a large and growing number of workers are finding only temporary and part time jobs.”

THIRD CLAIM: DECLINE IN PURCHASING POWER RESULTED IN MORTGAGE DEFAULT, HOUSING CRISIS, THUS THE GREAT RECESSION

“It should not, therefore, surprise anyone that in 2007, in the USA, the housing boom came to an end and home-owners began defaulting. It began with the subprime mortgages, but soon also the established working class and then the middle class started losing their ownership homes.”

“Trade unionists and all kinds of leftists may blame the current misery of the working people on brutal capitalist exploitation, on the weakness of the working class, on speculators without conscience, on greedy bankers, on globalization that has caused relocation of many production units to cheap-wage countries, etc. Of course, at first sight, all these explanations are partly correct. But on closer look one cannot but realize that when, on the whole, there are less and less resources to distribute because it is getting more and more difficult to extract them from nature….then, even in a better capitalist world with a strong working class, at best a fairer distribution could be achieved, not more property for all.” (emphasis in the original).

SARAL’S OWN SUMMARY: Saral summarizes his argument as follows:

“Workers in the broadest sense produce goods and services by using resources (including energy resources), tools and machines, which are also produced by using resources. If due to diminishing availability of affordable resources a growing number of workers lose their jobs or are forced to work only part-time, then they are producing no goods and services or less of them than before. Now, since most goods and services are, in the ultimate analysis, paid for by (exchanged with) goods and services, it is unavoidable that these workers can get less goods and services from other people.” (emphasis in the original).

3. Criticism

Each of the three claims outlined above is essential for the overall thesis of the essay. However, each claim is problematic as I will discuss below.

PROBLEMS WITH THE FIRST CLAIM: THERE IS NO EVIDENCE FOR A SECULAR, LASTING RISE FOR PRIMARY COMMODITY PRICES.

Let’s begin with noting that (1) Saral does not offer any time series data to support his claim for a secular rise in primary commodity prices, and, (2) he does not cite any references to the literature that establish such claim.

Thus, an undue burden is on his reader to verify this claim. I am not a natural resource economist who studies primary commodity prices. However, I took it upon myself to conduct a “first look” at the literature to help me think through Saral’s reasoning. I came away with the opposite of what he claims.

For Saral a secular, lasting rise of primary commodity prices is the cause of the Great Recession. However, the literature on primary commodity prices supports (1) that the shape rise in some primary commodity prices in the earlier part of the 2000s was the result of rapid industrialization in China and other “emerging economies,”and, (2) that this was a cyclical phenomenon not a secular and permanent change. In fact, soon after the crisis started primary commodity prices dropped.

Let’s take a look at some evidence from the literature on primary commodity prices. The investment bank and wealth manager Credit Suisse’s report (July 27, 2011) entitled “Long Run Commodity Prices: Where Do We Stand” (July 27, 2011) offers a detailed account. Exhibit 2 of this report shows a sharp rise of 210% in the Credit Suisse Commodities Benchmark since 2000. However, in the bank’s opinion, this was a cyclical rise in the index due to rapid and large demand.

“In our 13 January 2011 report, A Macroeconomic Proxy for Basic Materials Demand, we argue that much of the increase in commodity prices has been due to very strong commodity demand. As a complement to that analysis, this note assess prices against very long-run patterns, in an effort to establish where current prices are relative to the historical experience.

“While many economists and commentators have suggested that despite short-run volatility, over time commodity prices tend to fall, our analysis suggests that other than for agricultural products, most commodities do not have a clear long-run trend (up or down) with most effectively moving around a relatively consistent average over the past 110 years. Given the differences, to understand how recent movements fit within longer-run dynamics it is necessary to analyze each of the individual commodities.” (my emphases)

The rest of the report examines individual primary commodity prices. While some primary commodity prices, this report cites oil, iron ore and gold, were at their highest level in the past 110 years, others, like like grain prices are lower than historical average going back to 1850. Copper prices that Saral cites showed a sharp rise before the onset of the crisis in 2008 but they have dived down since and historical data shows a stable secular price (Appendix 1, Martin Stuermer, November 2013) . Prices of other metals, like Aluminum, have actually fallen during this entire period. For other studies that confirm the same the reader can consult Hirochi Yamada, March 2013, Steven McCorriston, June 2012.

Based on this evidence, I must conclude that (1) there is no secular and permanent rise in prices of the primary commodity prices taken as a group leading to the Great Recession, and (2) that the cyclical rise in the overall index was by driven mostly by oil and some metals as the consequences of increasingly industrialization demand from China and other “emerging economies,” and (3) that this cyclical rise in some primary commodity price was not a significant causal factor in the Great Recession. In fact, I know of no study that makes such a claim.

How about the supposed rise in the costs of environmental/ecological “services” that Saral claims? Saral offers no data or references to back up this claim. In a subsequent section given to a discussion of the GDP, Saral raises the problems of “defensive and compensatory costs” but there is no attempt to document them and link them empirically to the Great Recession.

While I entirely agree with the proposition that overtime production of some primary commodities will entail greater harm to nature and society, I feel unease with the notion of linking this phenomenon with the bourgeois economic doctrine as “defensive and compensatory costs.” The basic idea is that stock of physical, human and natural capital has to be replenished. To view humans and nature as “stock of capital” is an exercise in bourgeois alienation. In my view, such approach takes the discussion into the dominant economics (bourgeois) paradigm and undermines an alternative ecological socialist paradigm. The radical societal change will come only with a break with the economic (bourgeois) paradigm not in continuity with it. I will return to this in the last part of this commentary.

Since there was no secular rise in primary commodity prices and there is no evidence that a similar rise is the costs of environmental/ecological “services” hit the working masses purchasing power then these cannot be the cause of the massive mortgage default and the housing crisis in the U.S. as Saral claims. I have no choice but to conclude that Saral’s case for a “limits to growth” explanation of the Great Recession fails to get off the ground.

PROBLEMS WITH THE SECOND AND THIRD CLAIMS: WHY PURCHASING POWER OF THE WORKING PEOLLE FELL IN THE UNITED STATES?

But perhaps the rise in the cyclical prices of some commodity prices such as oil, iron ore and gold (that Credit Suisse report cites) or energy and metals as Saral claims squeezed the budget of working people and caused the housing crisis?

As I noted earlier, I know of no such a claim that is empirically supported. Still, it is an interesting hypothesis. However, even if one can show that a cyclical rise in price of some primary commodities contributed to the onset of the Great Recession it would not support a natural limits to growth argument. For that, one needs to establish a secular, long-term rise of primary commodities that form a significant portion of costs of mass production and consumption.

Further, how can any analysis ignore the economic and financial context of the mortgage default and the housing crisis, financial crisis when a firm like Lehman Brothers failed, AIG and the three giant automakers had to be rescued, and trillions of dollars were given to the biggest U.S. banks to remain solvent?

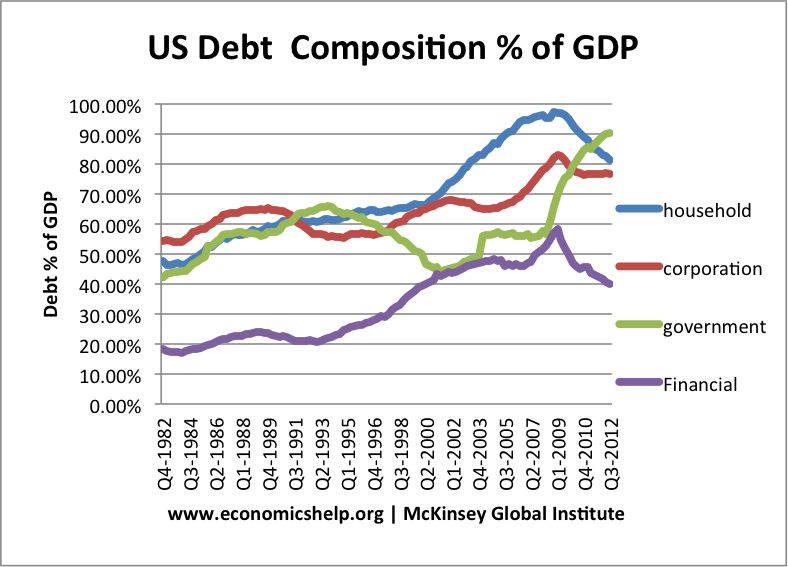

As the above figure from the McKinsey Global Institute shows, household debt, corporate debt and financial debt grew unsustainably from early 1980s to 2008. household debt was a staggering $12.68 trillion (100% of GDP), corporate debt about 85% of GDP and financial debt about %60 of GDP. The government debt fell through the Clinton years in part due to the fast growing economy (tax revenues increases) and in part due to austerity measure such as his signature “welfare reform” (cut in spendings). Given these data, it was not a question whether there will be a deep crisis but when and how it would break out.

Could anyone suggest that this long term exponential growth in debt was because of natural limits to growth? Or should we look elsewhere?

This commentary is not a place to discuss the causes of the Great Recession (there is never a single cause for a crisis of this proportion and there are many studies to cite and discuss). But we need to consider the financial conditions of the U.S. working class because of how Saral singles them out in his argument. The key fact to recall is the much studied and well understood phenomenon of declining real wage of workers and rising income inequality since the 1970s (for a journalist review of this see, for example, this 2012 Washington Post article) and this 2014 New York Times article).

Why have real wages fallen and income inequality risen? Because of a concentrated attack on the working class by the employers and their state. Why? To restore capitalist profitability.

As a number of Marxist economists established in a series of published academic articles in the 1980s and early 1990s (see various issues of Review for Radical Political Economics; also see references below for the explanation of the Great Recession that cover this period as well), the average rate of profit in the U.S. did decline from the end of World War II to the mid-1970s (marked by the world recession of 1973-75). A stagnation ensued. Keynesian policies added high inflation resulting in stagflation.

The capitalist class went of a neoliberal offensive marked by Thatcher and Reagan anti-labor offensive that targeted the miners union in Britain and the air traffic controllers union in the U.S. respectively. The assault also targeted the social wage resulting in Clinton’s “welfare reform” but has continued to targeting social security (retirement insurance), medicare (old age medical insurance) and medicaid (health insure for the very poor), food stamps, child nutrition program, etc. The assault has been comprehensive, targeting all earlier social gains from women’s right to safe abortion to environmental regulations to citizens’ right. And it has been internationalized.

Saral slights unionists, socialists and others for pointing out this frontal assault that has lasted now for well over three decades as “superficial” explanation for the crisis. However, with almost all productivity gains going to the top 1% of the population and continued use of fiscal and monetary policies to support various asset inflation schemes to combat stagnation of the U.S. economy (see, Laurence Summers's December 15, 2013 article), it is hard no to believe that bursting of the housing bubble had a non-economic, nonsocial cause. Seven years later, despite of lower primary commodity prices, historically low interest rate brought about by massive monetary policy intervention (basically a gift to the employer class), with corporations awash in cash, the U.S. economy is still dormant, Europe is toying with deflation, and China and the “emerging economies” facing a crisis. The key feature of the capitalist world economy in the past 40 years had been the dominance of financial capital; that is, those who Lenin called the coupon clippers.

Given all these facts, why not take a look at what the Marxists economists can provide as explanation for the Great Recession? Interested readers may consult Anwar Shaikh's, “The First Depression of the 21st Century” 2010; Fred Moseley’s, “The U.S. Economic Crisis” 2011; Duménil's and Levy’s The Crisis of Neoliberalism 2011; and Robert Brenner's “Reasons for the Great Recession” for a sample of such views.

So, why does Saral call Marx’s theory of the tendency of the rate of profit “unsatisfactory” and Marxist explanations of the Great Recession “superficial?” What alternative theory of the capitalist system would Saral propose or endorse? After all, anyone who wants to analyze any aspect of the functioning of the capitalist system should begin with some theory of the beast and how it lives.

In fact, Saral’s own essay reveal this necessity. For example, he attribute the “usual inflations of the past” to mainly “high wage demands of the working people (the so-called wage-price spiral).” But what does constitute “high wage demand by the working people?” High by whose standard? Further if real wages have been falling for 40 years what accounts for the stagflation in the U.S. in the 1970s? It could not have been high wage demands, or could it? Is not “wage-price spiral” argument part of the mainstream (bourgeois) macroeconomic theory that blames workers for capitalist inflation (the other is “demand spiral,” commodity demand)? Why should an ecological socialist subscribe to such an anti-labor “theory”? What is wrong, for example, with Marx’s argument in Wage, Price and Profit (1865)?

Similarly, in the summary of his argument quoted above Saral argues that due to “diminishing availability of affordable resources a growing number of workers lose their jobs or are forced to work only part-time, then they are producing no goods and services or less of them than before.” Again, the problem of unemployment and falling standards of living, including increasing nutritional deficiency, homelessness, lack of health insurance, and misery of the working people in the United States is blamed not on the capitalist anti-labor policies but on the nature law of diminishing returns.

4. Limits to the Limits to Growth Perspective

To conclude this commentary, it is necessary to place the limits to growth argument in context.

A. The Historical Context

Limits to Growth (1972) was the title of the first report commissioned by the international think-tankClub of Rome. The report has been updated every 10 years since. The 1972 report’s authors, Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, used a computer model they built and named World3 to simulate the consequence of interactions between the Earth's and human systems focusing on the exponential economic and population growth dynamics in the face of finite resources.

A key finding was that

"If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years. The most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.” (Limits to Growth, p. 23, 1972)

The publication of Limits to Growth stirred much interest and debate but also much hostility that eventually derailed the healthy discussion that ensued. The hostility to Limits to Growth came largely from the free marketeers on the right whose ideology is wedded to the 250 years capitalist growth and industrialization.

The socialist critique of the Limits to Growth also included an ideological bias for growth perceived as progress (in Marxist ideology growth of “forces of production” is desirable). The bias is most visible in socialist hostility to all criticism of exponential human population growth as “Malthusian,” that is reactionary and anti-working class. However, the socialist critique included a valid point. Limits to Growth model incorporates many assumptions based on mainstream socio-economic theories. That is, Limits to Growth proponents sidelined, if not entirely denied, economic, social and ideological criticism of the capitalist system in favor of arguing for natural limits to growth. It was argued that if these natural limits are not respected the population and the economy will go into a sudden and precipitous decline. Of course, the reality of the present day world includes all such limits, economic, social, and natural, to the capitalist civilization.

B. Limits to Growth and Green Capitalism

Thus, the authors of the report and Club of Rome have not rule out socially and ecologically “sustainable capitalism” or “sustainable growth” if “appropriate measures” are taken in time. In 1972, they wrote:

"It is possible to alter these growth trends and to establish a condition of ecological and economic stability that is sustainable far into the future. The state of global equilibrium could be designed so that the basic material needs of each person on earth are satisfied and each person has an equal opportunity to realize his individual human potential.” (Ibid, p. 24)

As a result Limits to Growth has largely served as an intellectual platform for the Green Capitalism ideology. One of the original authors of the 1972 report, Jørgen Randers, has recently published 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years (2012) that scales back some of the earlier more alarmist predictions (e.g. in case of energy), avoids making predictions and offers proposals for individual action (not systemic proposals).

At the fringe are a small number of ecological socialists and anarchists who subscribe to the general notion that there are natural limits to growth but retain a critical attitude towards the existing capitalist order and Green Capitalism. We should value Eco-socialism or Eco-Capitalism (1999) where Saral devotes the bulk of the book to refute Green Capitalism. At the same time, he correctly criticizes the productivist vision of socialism. Both these contributions make the book a must read for anyone interested in ecological socialism.

Thus, to adopt a natural limit to growth perspective it is necessary to link it to a critical social theory that can explain how we have arrived at the current critical juncture in history and how to overcome the existing globalized capitalist system that has generated and perpetuates the conditions causing the crisis.

C. Limits to Growth and Externalities

In his essay, Saral devotes a section to a criticism of the GDP using K. William Kapp's criticism of the GDP accounting for not addressing “defensive” and “compensatory” costs defined as costs to replenish physical, human and natural capital. Kapp is considered the founder of ecological economics, a discipline dedicated to integrating the environmental and ecological aspect of the economy into the mainstream theory.

“Defensive” and “compensatory” costs are externalities defined as cost or benefit of economic activities to third parties or society at large. The negative externality is pervasive and well known such as industrial pollution. The positive externalities alexiststs. A bee keeper’s price of honey does not reflect the gain from pollination in the almond orchard next door. Market failure refers to the failure of the price mechanism to capture such costs or benefits. It should surprise no one that these costs and benefits are not included in the GDP. One could, as Kapp and ecological economists have tried, attempt to do so. However, it is not a prudent approach and that it cannot possibly succeed. How does one go about economic account for all types of ecocide, pain and suffering of farm animals, mass extinction of species, melting of the Earth’s ice caps? Arguments for amending the GDP to account for various externalities are made within the economics (bourgeois) paradigm regardless of anyone’s intent. Concerns for the species going extinct is made from an ecocentric paradigm even if those who make it don’t realize it. The two paradigms are not reconcilable.

On the other hand, the limit to growth argument offers a powerful argument for a rise in negative externalities and decline of the positive externalities (witness the plight of the honey bee or bats, both are major pollinators). Whereas cost of production of natural resources will increase given enough time due to diminishing returns it is quite possible that prices decline in intermediate terms using new technologies. But negative externalities are likely to increase. Thus, from an ecological point of view, the costs outstrip the benefits while from an economic point of view it is the other way around. Just consider fracking for natural gas, shale oil and mountain top mining for coal.

Thus, it is more fruitful to use limits to growth perspective as a way to discuss increasing environmental and ecological costs than to try to use it as the exclusive or “deeper” cause for the Great Recession.

D. Limits to Growth as a Paradigm

Saral and others have talked about natural limits to growth a as paradigm shift. In a sense it is. Socialist and most other radical traditions have focused on social and economic issues. The growth paradigm has become part of these traditions as critical as they are of the capitalist system. Natural limits to growth offers a new way to think about contradictions of class societies. I say this being fully aware that Saral and other supporters of limits to growth perspective mostly or exclusively focus of industrial societies. But if one accepts the fact of ecological/environmental cause for the decline and disappearance of pre-industrial civilizations then it becomes clear the limits to growth has operated throughout human history and, in some instances, even prehistory. It’s impact in the earlier times was local or regional. Under industrial globalized capitalist system it’s impact is planetary.

Therefore, without denying the specificity of natural limits to growth in an industrial global capitalist economy, it is clear that the problem is common to all civilizations since the dawn of agriculture. At issue is nothing less than our species relation with the rest of nature. But limits to growth does not provide us with a philosophy of nature or anything about who we are, where we come from and where we are going. Thus, Limits to Growth of the Club of Rome, if taken as a paradigm, may offer a technical approach to nature the as provider of “resources" and “services” but not an ethical perspective for a good society.

For all who argue for a scaled back “sustainable” communal human society, the key question is how scaled back and what such sustainability entails for the lives of other species? Would that be defined simply by technical requirements to maintain a sustainable stock of other species and some balance in ecosystems to meet our needs for food, shelter, and fun or by adhering to a philosophy of nature that affords similar rights to all species to live their full natural potential?

In Economics, Socialism and Ecology, Part 2, I have argued that the crisis we face is really a crisis of the anthropocentric civilization that has manifested itself as the crisis of the industrial capitalist system. Civilization has been built on farming that requires alienation from nature. Our species that has viewed itself an integral part of the nature and practiced ecocentric cultures for millions of years has come to institutionalize an anthropocentric culture that aims to control and dominate nature. Social alienation, manifested by social segmentation of all kinds, including through class and state formation as well as markets (especially under the capitalist system) have rested on alienation from nature. All different modes of production and social formations since the Agricultural Revolution have been built towards the goal of controlling and exploiting nature. That, of course, included exploitation of other human beings.

I submit that ecological socialism and anarchism or any other emancipatory movement should be based not on any natural, social or economic limits to growth but on a positive world movement to reintegrate ourselves with the rest of nature that includes embracing all the of humanity in its many creative and enriching potentials.

Notes:

1. Saral’s essay is dated August 28, 2010, but was sent for publication in Our Place in the World a few weeks ago. The essay contains other issues that need critical discussion. However, I am focusing on the section that argues for limits to growth cause of the Great Recession.

2. There is a table on page 269 of Saral’s book The Crises of Capitalism (2012) that show these costs rise somewhat in the Federal Republic of Germany during the 1970-1988 period. While this is suggestive that the same may have been happening in the U.S. it is necessary to document these and show their causal connection to the Great Recession.

3. The Club of Rome was founded in 1968 “as an informal association of independent leading personalities from politics, business, and science, men and women who are long-term thinkers interested in contributing in a systemic interdisciplinary and holistic manner to a better world. The Club of Rome members shares a common concern for the future of humanity and the planet.” (from Club of Rome website)

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/Futurism-Got-Corn-graph-631.jpg)